The goddess Hera, determined to make trouble for Hercules, made him lose his mind. In a confused and angry state, he killed his own wife and children.

When he awakened from his "temporary insanity," Hercules was shocked and upset by what he'd done. He prayed to the god Apollo for guidance, and the god's oracle told him he would have to serve Eurystheus, the king of Tiryns and Mycenae, for twelve years, in punishment for the murders.

As part of his sentence, Hercules had to perform twelve Labors, feats so difficult that they seemed impossible. Fortunately, Hercules had the help of Hermes and Athena, sympathetic deities who showed up when he really needed help. By the end of these Labors, Hercules was, without a doubt, Greece's greatest hero.

His struggles made Hercules the perfect embodiment of an idea the Greeks called pathos, the experience of virtuous struggle and suffering which would lead to fame and, in Hercules' case, immortality.

The Nemean Lion

Initially, Hercules was required to complete ten labors, not twelve. King Eurystheus decided Hercules' first task would be to bring him the skin of an invulnerable lion which terrorized the hills around Nemea.

Nemea, Temple of Zeus and landscape

Overall view from SW

Photograph courtesy of the Department of Archaeology, Boston University, Saul S. Weinberg Collection

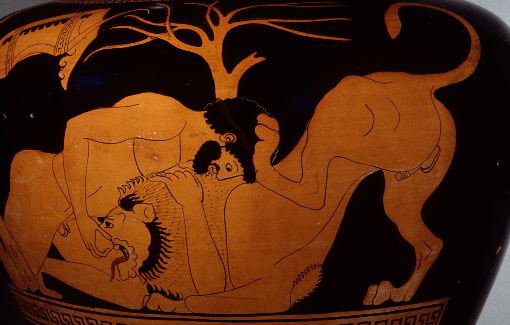

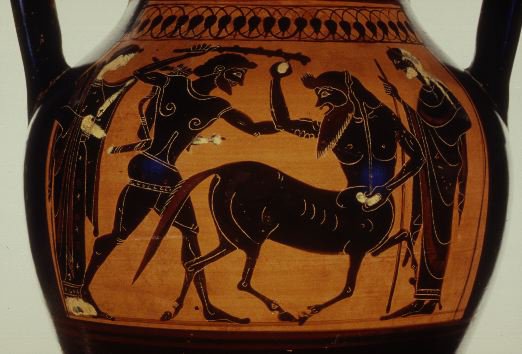

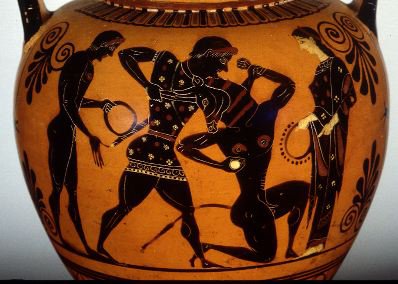

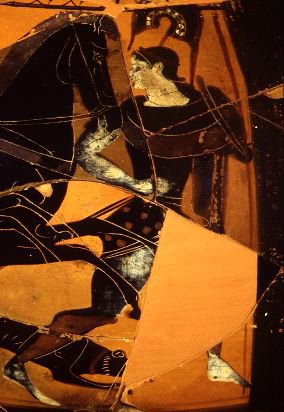

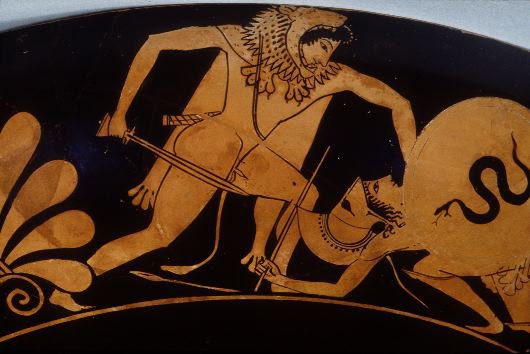

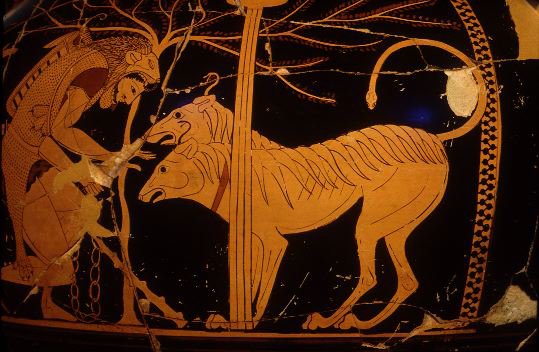

Hercules wrestling the Nemean Lion

Philadelphia L-64-185, Attic red figure stamnos, ca. 490 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum

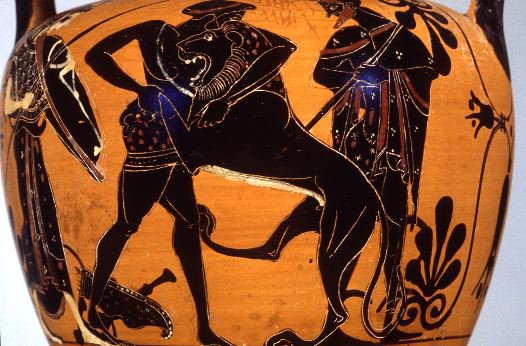

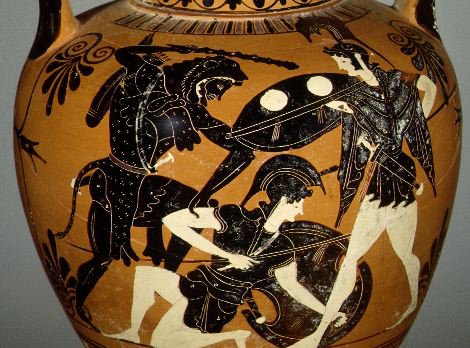

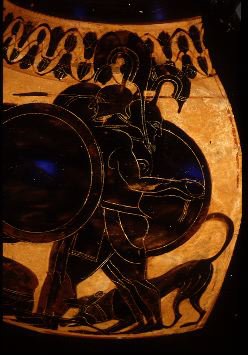

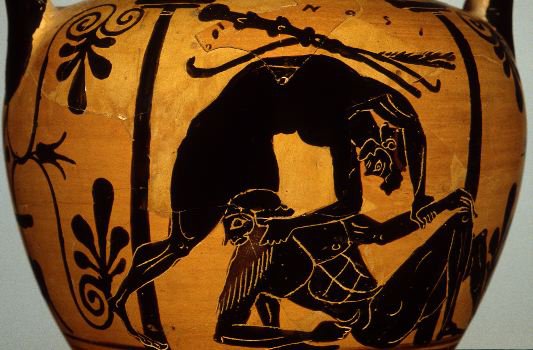

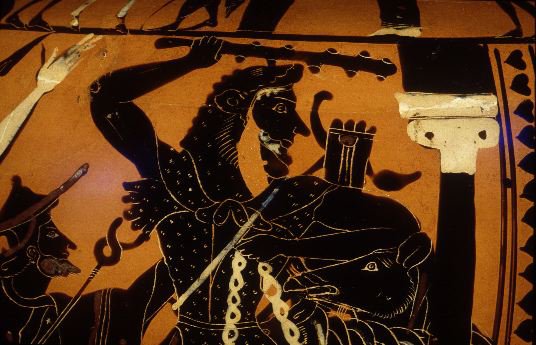

Hercules wrestling the Nemean lion

Mississippi 1977.3.62, Attic black figure neck amphora, ca. 510-500 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University Museums, University of Mississippi

When Hercules made it back to Mycenae, Eurystheus was amazed that the hero had managed such an impossible task. The king became afraid of Hercules, and forbade him from entering through the gates of the city. Furthermore, Eurystheus had a large bronze jar made and buried partway in the earth, where he could hide from Hercules if need be. After that, Eurystheus sent his commands to Hercules through a herald, refusing to see the powerful hero face to face.

Hercules wearing the lion skin

Boston 99.538, Attic bilingual amphora, ca. 525-500 B.C.

Photograph courtesy,Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. H. L. Pierce Fund

First he cleared the grove of Zeus of a lion, and put its skin upon his back, hiding his yellow hair in its fearful tawny gaping jaws. Euripides, Hercules, 359

The Lernean Hydra

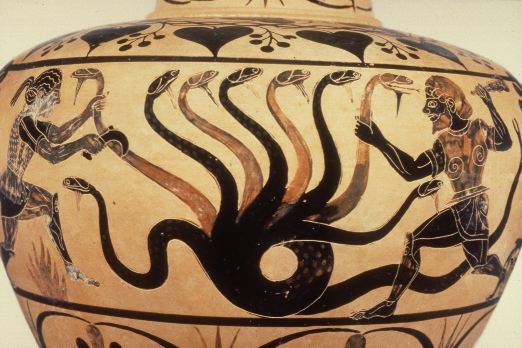

The second labor of Hercules was to kill the Lernean Hydra. From the murky waters of the swamps near a place called Lerna, the hydra would rise up and terrorize the countryside. A monstrous serpent with nine heads, the hydra attacked with poisonous venom. Nor was this beast easy prey, for one of the nine heads was immortal and therefore indestructible.

Lerna

Aerial view of site and bay, from E

Photograph by Raymond V. Schoder, S.J., courtesy of Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers

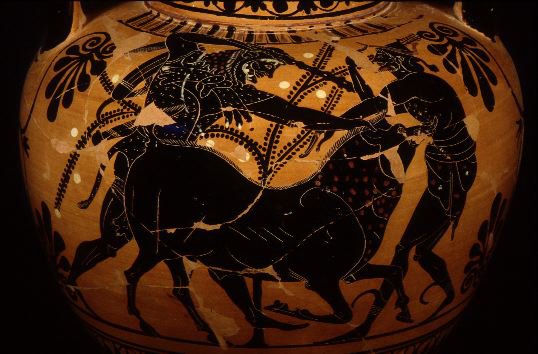

Munich 1416, Attic black figure amphora, ca. 510-500 B.C.

Side A: scene at left, Hercules and Iolaos in chariot

Photograph copyright Staatl. Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, München

Each time Hercules bashed one of the hydra's heads, Iolaus held a torch to the headless tendons of the neck. The flames prevented the growth of replacement heads, and finally, Hercules had the better of the beast. Once he had removed and destroyed the eight mortal heads, Hercules chopped off the ninth, immortal head. This he buried at the side of the road leading from Lerna to Elaeus, and for good measure, he covered it with a heavy rock. As for the rest of the hapless hydra, Hercules slit open the corpse and dipped his arrows in the venomous blood.

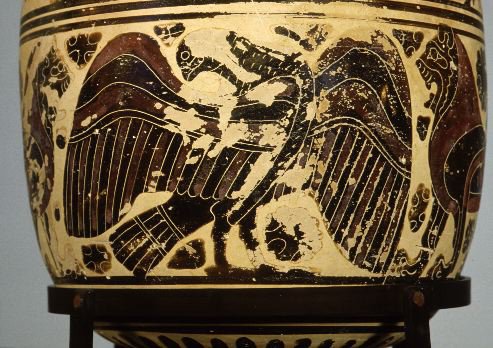

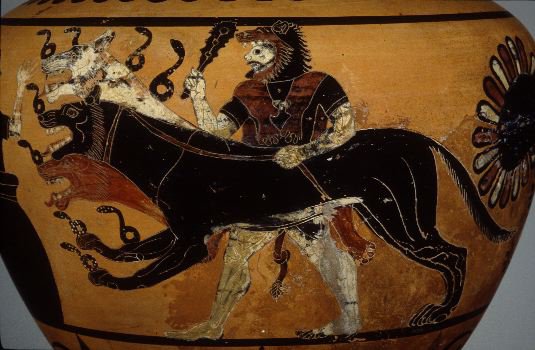

Malibu 83.AE.346, Caeretan hydria, c. 525 B.C.

Main panel: Hercules slaying the Lernean hydra

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

At the source of the Amymone grows a plane tree, beneath which, they say, the hydra (water-snake) grew. I am ready to believe that this beast was superior in size to other water-snakes, and that its poison had something in it so deadly that Heracles treated the points of his arrows with its gall. It had, however, in my opinion, one head, and not several. It was Peisander of Camirus who, in order that the beast might appear more frightful and his poetry might be more remarkable, represented the hydra with its many heads. Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.37.4

The Hind of Ceryneia

Diana's Pet Deer

For the third labor, Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the Hind of Ceryneia. Now, before we go any further, we'll have to answer two questions: What is a hind? and, Where is Ceryneia?Diana's Pet Deer

Ceryneia is a town in Greece, about fifty miles from Eurystheus' palace in Mycenae.

Map of Southern Greece showing Ceryneia and Mycenae

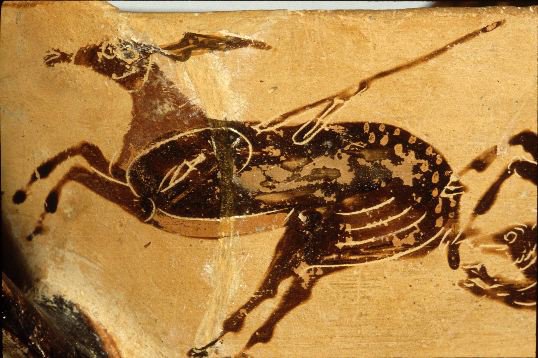

Deer pursued by hunters

Harvard 1960.390, Boeotian black figure kantharos, ca. 560-550 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

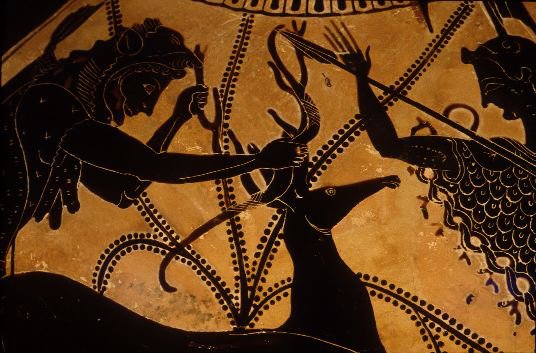

Hercules with the hind of Ceryneia and the goddess Athena

Toledo 1958.69a+b, Attic black figure pointed amphora, ca. 510 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Diana was very angry because Hercules tried to kill her sacred animal. She was about to take the deer away from Hercules, and surely she would have punished him, but Hercules told her the truth. He said that he had to obey the oracle and do the labors Eurystheus had given him. Diana let go of her anger and healed the deer's wound. Hercules carried it alive to Mycenae.

Diana with a deer

Mississippi 1977.3.117, Attic red figure, white ground lekythos, ca. 480-470 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University Museums, University of Mississippi

The Erymanthian Boar

For the fourth labor, Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the Erymanthian boar alive. Now, a boar is a huge, wild pig with a bad temper, and tusks growing out of its mouth.

Dewing 2440, silver stater from Lycia in Asia Minor, c. 520-500 B.C.

Obverse: the forepart of a boar.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Dewing Numismatic Foundation

Malibu 86.AE.154, Attic black figure Siana cup, c. 580-570 B.C.

A boar hunt.

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

London B 226, Attic black figure neck amphora, c. 530-510 B.C.

Hercules and the centaur Pholos shaking hands.

Photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London

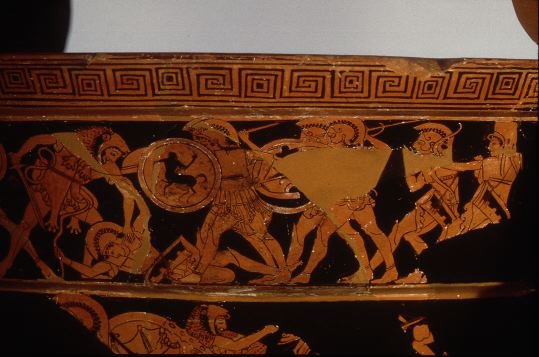

Soon afterwards, the rest of the centaurs smelled the wine and came to Pholus's cave. They were angry that someone was drinking all of their wine. The first two who dared to enter were armed with rocks and fir trees.

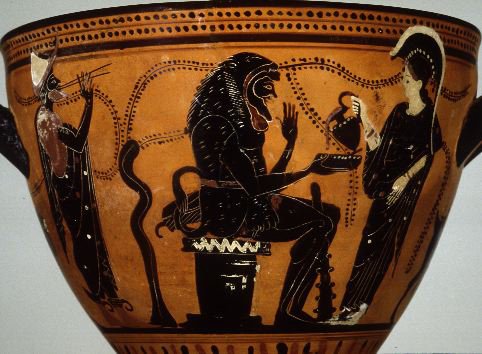

RISD 22.215, Apulian red figure calyx krater, c. 430-420 B.C.

A centaur holds a rock, poised to attack Hercules.

Photograph by Brooke Hammerle, courtesy of the Museum of Art, RISD, Providence, RI

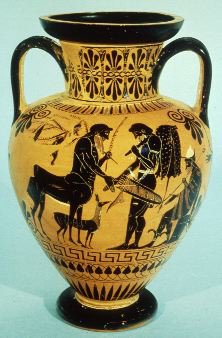

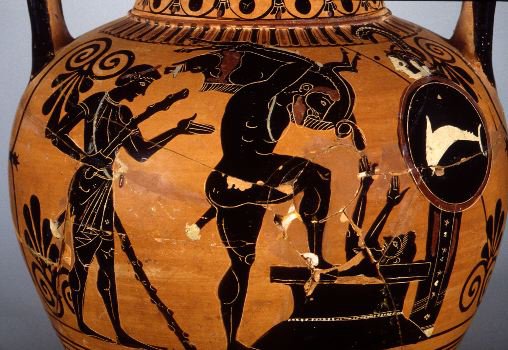

Malibu 88.AE.24, Attic black figure amphora, c. 530-520 B.C.

Hercules rauses his club, about to hit a centaur.

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

While Hercules was gone, Pholus pulled an arrow from the body of one of the dead centaurs. He wondered that so little a thing could kill such a big creature. Suddenly, the arrow slipped from his hand. It fell onto his foot and killed him on the spot. So when Hercules returned, he found Pholus dead. He buried his centaur friend, and proceeded to hunt the boar.

It wasn't too hard for Hercules to find the boar. He could hear the beast snorting and stomping as it rooted around for something to eat. Hercules chased the boar round and round the mountain, shouting as loud as he could. The boar, frightened and out of breath, hid in a thicket. Hercules poked his spear into the thicket and drove the exhausted animal into a deep patch of snow.

Harvard 1960.314, Attic black figure neck amphora, c. 510-500 B.C.

Hercules grabs the boar's head and raises his club to strike it. On the right, the god Hermes offers assistance.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

Hercules brings the boar to Eurstheus, carrying it on his shoulder. He rests his foot on the rim of the pithos, where Eurystheus cowers.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University Museums, University of Mississippi

The Augean Stables

Hercules Cleans Up

Hercules Cleans Up

For the fifth labor, Eurystheus ordered Hercules to clean up King Augeas' stables. Hercules knew this job would mean getting dirty and smelly, but sometimes even a hero has to do these things. Then Eurystheus made Hercules' task even harder: he had to clean up after the cattle of Augeas in a single day.

Now King Augeas owned more cattle than anyone in Greece. Some say that he was a son of one of the great gods, and others that he was a son of a mortal; whosever son he was, Augeas was very rich, and he had many herds of cows, bulls, goats, sheep and horses.

An aerial view of Olympia in Elis, where Augeas ruled his kingdom.

Photograph by Raymond V. Schoder, S.J., courtesy of Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers

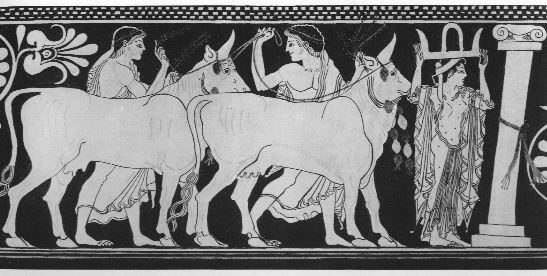

Boston 13.195, Attic red figure lekythos, c. 530-500 B.C.

People leading cows.

From Caskey & Beazley, plate IV. With permission of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

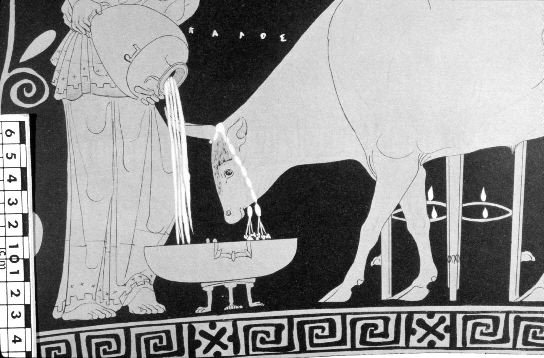

Munich 2412, Attic red figure stamnos, c. 440-430 B.C.

A bull drinking water from a basin.

From Furtwängler & Reichhold, pl. 19

Next, he dug wide trenches to two rivers which flowed nearby. He turned the course of the rivers into the yard. The rivers rushed through the stables, flushing them out, and all the mess flowed out the hole in the wall on other side of the yard.

Mount Holyoke 1925.BS.II.3, Attic black figure skyphos, c. 500 B.C.

Hercules takes a break. The goddess Athena pours him a cup of wine.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

The judge took his seat. Hercules called the son of Augeas to testify. The boy swore that his father had agreed to give Hercules a reward. The judge ruled that Hercules would have to be paid. In a rage, Augeas ordered both his own son and Hercules to leave his kingdom at once. So the boy went to the north country to live with his aunts, and Hercules headed back to Mycenae. But Eurystheus said that this labour didn't count, because Hercules was paid for having done the work.

The Stymphalian Birds

After Hercules returned from his success in the Augean stables, Eurystheus came up with an even more difficult task. For the sixth Labor, Hercules was to drive away an enormous flock of birds which gathered at a lake near the town of Stymphalos.Arriving at the lake, which was deep in the woods, Hercules had no idea how to drive the huge gathering of birds away. The goddess Athena came to his aid, providing a pair of bronze krotala, noisemaking clappers similar to castanets. These were no ordinary noisemakers. They had been made by an immortal craftsman, Hephaistos, the god of the forge.

Dancer with krotala, flute case, and walking stick

Philadelphia MS2445, Attic red figure kylix, ca. 480 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum

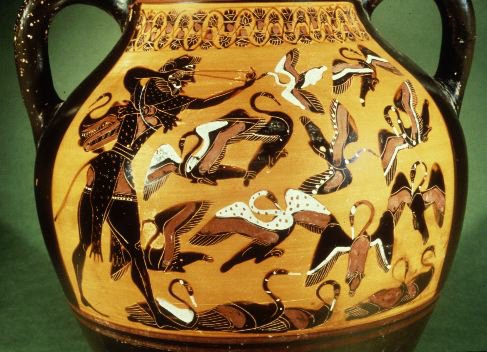

Hercules and the Stymphalian birds

London B 163, Attic black figure amphora, ca. 560-530 B.C.

Photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London

| These fly against those who come to hunt them, wounding and killing them with their beaks. All armor of bronze or iron that men wear is pierced by the birds; but if they weave a garment of thick cork, the beaks of the Stymphalian birds are caught in the cork garment... These birds are of the size of a crane, and are like the ibis, but their beaks are more powerful, and not crooked like that of the ibis. Pausanias, Description of Greece, 8.22.5 |

The Cretan Bull

After the complicated business with the Stymphalian Birds, Hercules easily disposed of the Cretan Bull.At that time, Minos, King of Crete, controlled many of the islands in the seas around Greece, and was such a powerful ruler that the Athenians sent him tribute every year. There are many bull stories about Crete. Zeus, in the shape of a bull, had carried Minos' mother Europa to Crete, and the Cretans were fond of the sport of bull-leaping, in which contestants grabbed the horns of a bull and were thrown over its back.

Bull fresco from the Palace of Minos in Knossos

Photograph courtesy of the Department of Archaeology, Boston University, Saul S. Weinberg Collection

When Hercules got to Crete, he easily wrestled the bull to the ground and drove it back to King Eurystheus. Eurystheus let the bull go free. It wandered around Greece, terrorizing the people, and ended up in Marathon, a city near Athens.

|  |

| Hercules ropes the Cretan Bull Mississippi 1977.3.61a and b, Attic black figure neck amphora, ca. 530-520 B.C. Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University Museums, University of Mississippi | Hercules drives the bull back to Mycenae Boston 99.538, Attic bilingual amphora, ca. 525-500 B.C. From Caskey & Beazley, plate LXVII. With permission of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Theseus fighting the Minotaur

RISD 25.083, Attic black figure amphora, ca. 550-530 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Museum of Art, RISD, Providence, RI

The Man-Eating Horses of Diomedes

After Hercules had captured the Cretan Bull, Eurystheus sent him to get the man-eating mares of Diomedes, the king of a Thracian tribe called the Bistones, and bring them back to him in Mycenae.

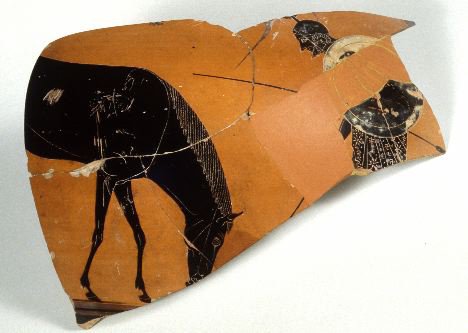

Warrior approaching grazing horse

Philadelphia MS4873, fragment of an Attic black figure amphora, ca. 540 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum

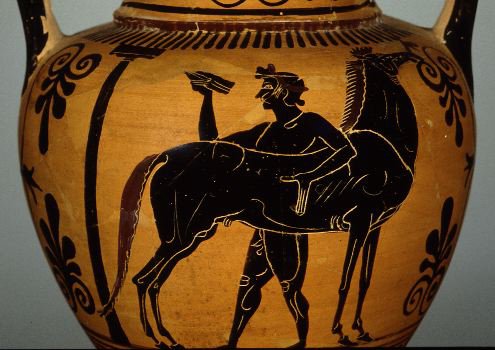

Horse and groom

Tampa 86.29, Attic black figure neck amphora, ca. 490-480 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Tampa Museum of Art

Fallen archer trampled by horses

Tampa 86.41, Attic black figure oinochoe, ca. 510 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Tampa Museum of Art

Abdera

Overall view of city gate from outside, from NW

Photograph by Beth McIntosh and Sebastian Heath

Euripides gives two different versions of the story, but both of them differ from Apollodorus's in that Hercules seems to be performing the labor alone, rather than with a band of followers. In one, Diomedes has the four horses harnessed to a chariot, and Hercules has to bring back the chariot as well as the horses. In the other, Hercules tames the horses from his own chariot:

He mounted on a chariot and tamed with the bit the horses of Diomedes, that greedily champed their bloody food at gory mangers with unbridled jaws, devouring with hideous joy the flesh of men. Euripides, Hercules, 380

Hippolyte's Belt

Hercules Fights the Amazons

For the ninth labor, Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the belt of Hippolyte [Hip-POLLY-tee]. This was no ordinary belt and no ordinary warrior. Hippolyte was queen of the Amazons, a tribe of women warriors. Hercules Fights the Amazons

Mississippi 1977.3.57, Attic black figure neck amphora, c. 530-520 B.C.

Side A: Amazon on left, detail

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University Museums, University of Mississippi

The Amazons lived apart from men, and if they ever gave birth to children, they kept only the females and reared them to be warriors like themselves.

Queen Hippolyte had a special piece of armor. It was a leather belt that had been given to her by Ares, the war god, because she was the best warrior of all the Amazons. She wore this belt across her chest and used it to carry her sword and spear. Eurystheus wanted Hippolyte's belt as a present to give to his daughter, and he sent Hercules to bring it back.

Hercules' friends realized that the hero could not fight against the whole Amazon army by himself, so they joined with him and set sail in a single ship.

London B 436, Attic black figure kylix, c. 540-500 B.C.

A warship with mast and sail. Its prow is in the form of a boar's head, and it has a high fore-deck, steering oars and a landing ladder at the stern. Eight figures can be seen rowing the upper set of oars (there are at least as many people on the lower deck) and the sail is fully extended, giving the impression that the boat is moving "full speed ahead."

Photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London

Philadelphia MS4832, Attic black figure amphora, c. 525-500 B.C.

Amazon running, with her dog along side.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum

Malibu 77.AE.11, Attic red figure volute krater, c. 490 B.C.

Amazons arming.

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

Mississippi 1977.3.243, Attic red figure white ground pyxis, c. 460-450 B.C.

Amazon on horseback.

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

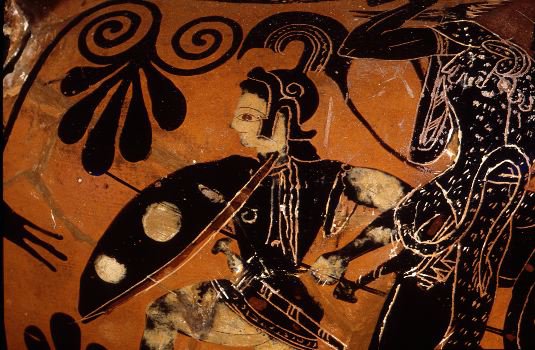

Tampa 82.11.1, Attic black figure neck amphora, c. 510-500 B.C.

Hercules battles the Amazons. The Amazon has fallen to one knee, supported by the shield on her left arm. A wrapped object at her waist may represent the prized belt.

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

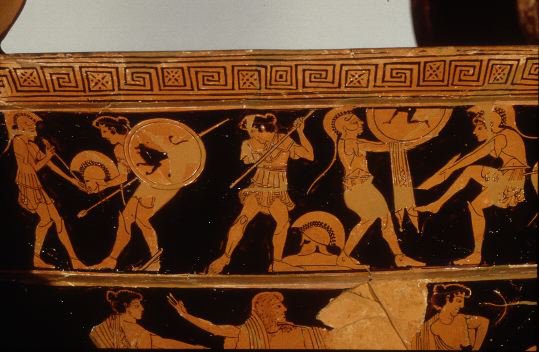

Hercules and the Greeks fought the rest of the Amazons in a great battle.

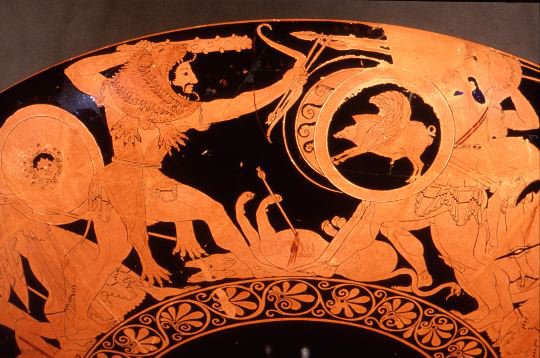

Malibu 77.AE.11, Attic red figure volute krater, c. 490 B.C.

Hercules fighting the Amazons.

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

The Cattle of Geryon

To accomplish his tenth labor, Hercules had to journey to the end of the world. Eurystheus ordered the hero to bring him the cattle of the monster Geryon. Geryon was the son of Chrysaor and Callirrhoe. Chrysaor had sprung from the body of the Gorgon Medusa after Perseus beheaded her, and Callirrhoe was the daughter of two Titans, Oceanus and Tethys. With such distinguished lineage, it is no surprise that Geryon himself was quite unique. It seems that Geryon had three heads and three sets of legs all joined at the waist. | And the daughter of Ocean, Callirrhoe... bore a son who was the strongest of all men, Geryones, whom mighty Heracles killed in sea-girt Erythea for the sake of his shambling oxen. Hesiod, Theogony, 980 |

Harvard 1972.42, Attic black figure amphora, c. 550-530 B.C.

Side A: Geryon

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

Sailing in a goblet which the Sun gave him in admiration, Hercules reached the island of Erythia. Not long after he arrived, Orthus, the two-headed dog, attacked Hercules, so Hercules bashed him with his club. Eurytion followed, with the same result. Another herdsman in the area reported these events to Geryon. Just as Hercules was escaping with the cattle, Geryon attacked him. Hercules fought with him and shot him dead with his arrows.

Munich 2620, Attic red figure kylix, c. 510-500 B.C.

Side A: Hercules, Geryon, the dog Orthros

Photograph copyright Staatl. Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, München

The escaped bull was found by a ruler named Eryx, another of Poseidon's sons, and Eryx put this bull into his own herd. Meanwhile, Hercules was searching for the runaway animal. He temporarily entrusted the rest of the herd to the god Hephaestus, and went after the bull. He found it in Eryx's herd, but the king would return it only if the hero could beat him in a wrestling contest. Never one to shy away from competition, Hercules beat Eryx three times in wrestling, killed the king, took back the bull, and returned it to the herd.

RISD 26.166, Apulian red figure rhyton (drinking cup), c. 400-300 B.C.

Drinking cup in the shape of a bull's head.

Photograph by Brooke Hammerle, courtesy of the Museum of Art, RISD, Providence, RI

Possible return route of Hercules with the cattle of Geryon.

The Apples of the Hesperides

Poor Hercules! After eight years and one month, after performing ten superhuman labors, he was still not off the hook. Eurystheus demanded two more labors from the hero, since he did not count the hydra or the Augean stables as properly done.Eurystheus commanded Hercules to bring him golden apples which belonged to Zeus, king of the gods. Hera had given these apples to Zeus as a wedding gift, so surely this task was impossible. Hera, who didn't want to see Hercules succeed, would never permit him to steal one of her prize possessions, would she?

These apples were kept in a garden at the northern edge of the world, and they were guarded not only by a hundred-headed dragon, named Ladon, but also by the Hesperides, nymphs who were daughters of Atlas, the titan who held the sky and the earth upon his shoulders.

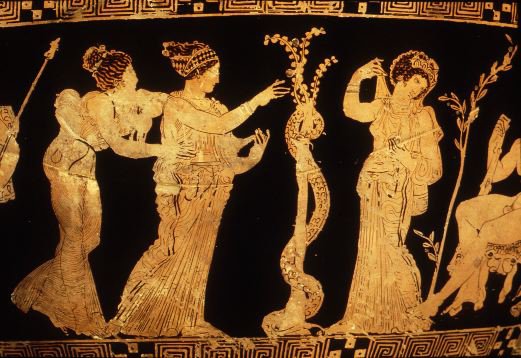

The Hesperides in the garden. Here the apples are on a tree, and the dragon Ladon looks more like a single-headed serpent.

London E 224, Attic red figure hydria, ca. 410-400 B.C.

Photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London

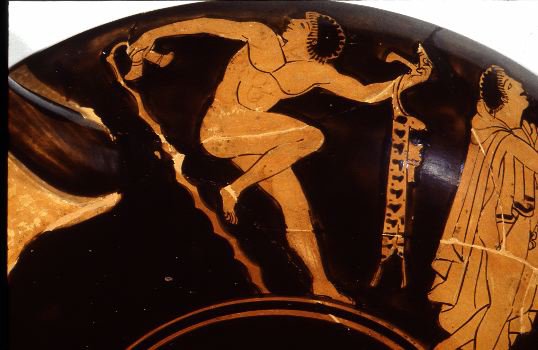

Hercules fighting Kyknos

Toledo 1961.25, Attic red figure kylix, ca. 520-510 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

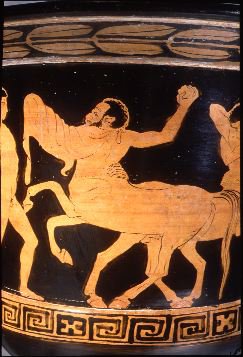

Hercules wrestling Antaeus

Tampa 86.29, Attic black figure neck amphora, ca. 490-480 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Tampa Museum of Art

Eagle with wings outstretched.

Philadelphia MS553, Corinthian alabastron, ca. 620-590 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University of Pennyslvania Museum

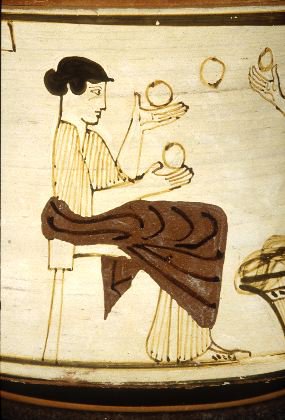

Woman juggling apples.

Toledo 1963.29, Attic red figure, white ground pyxis, ca. 470-460 B.C.

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

There was one final problem: because they belonged to the gods, the apples could not remain with Eurystheus. After all the trouble Hercules went through to get them, he had to return them to Athena, who took them back to the garden at the northern edge of the world.

Hercules in the garden of the Hesperides.

Sometimes the hero is portrayed in the garden, even though the story we have from Apollodorus is that he sent Atlas there instead of going himself.

London E 224, Attic red figure hydria, ca. 410-400 B.C.

Photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London

Cerberus

The most dangerous labor of all was the twelfth and final one. Eurystheus ordered Hercules to go to the Underworld and kidnap the beast called Cerberus (or Kerberos). Eurystheus must have been sure Hercules would never succeed at this impossible task! The ancient Greeks believed that after a person died, his or her spirit went to the world below and dwelled for eternity in the depths of the earth. The Underworld was the kingdom of Hades, also called Pluto, and his wife, Persephone. Depending on how a person lived his or her life, they might or might not experience never-ending punishment in Hades. All souls, whether good or bad, were destined for the kingdom of Hades.

Toledo 1969.371

Main panel:Hercules and Cerberus, upper half

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

| . . . A monster not to be overcome and that may not be described, Cerberus who eats raw flesh, the brazen-voiced hound of Hades, fifty-headed, relentless and strong. Hesiod, Theogony 310 |

Among the children attributed to this awful couple were Orthus (or Othros), the Hydra of Lerna, and the Chimaera. Orthus was a two-headed hound which guarded the cattle of Geryon. With the Chimaera, Orthus fathered the Nemean Lion and the Sphinx. The Chimaera was a three-headed fire-breathing monster, part lion, part snake, and part goat. Hercules seemed to have a lot of experience dealing with this family: he killed Orthus, when he stole the cattle of Geryon, and strangled the Nemean Lion. Compared to these unfortunate family members, Cerberus was actually rather lucky.

Louvre F 204

Side A: Kerberos

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Musée du Louvre

Hercules went to a place called Taenarum in Laconia. Through a deep, rocky cave, Hercules made his way down to the Underworld. He encountered monsters, heroes, and ghosts as he made his way through Hades. He even engaged in a wrestling contest! Then, finally, he found Pluto and asked the god for Cerberus. The lord of the Underworld replied that Hercules could indeed take Cerberus with him, but only if he overpowered the beast with nothing more than his own brute strength.

A weaponless Hercules set off to find Cerberus. Near the gates of Acheron, one of the five rivers of the Underworld, Hercules encountered Cerberus. Undaunted, the hero threw his strong arms around the beast, perhaps grasping all three heads at once, and wrestled Cerberus into submission. The dragon in the tail of the fierce flesh-eating guard dog bit Hercules, but that did not stop him. Cerberus had to submit to the force of the hero, and Hercules brought Cerberus to Eurystheus. Unlike other monsters that crossed the path of the legendary hero, Cerberus was returned safely to Hades, where he resumed guarding the gateway to the Underworld. Presumably, Hercules inflicted no lasting damage on Cerberus, except, of course, the wound to his pride!

Louvre E 701

Main panel: Hercules and Kerberos

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Musée du Louvre