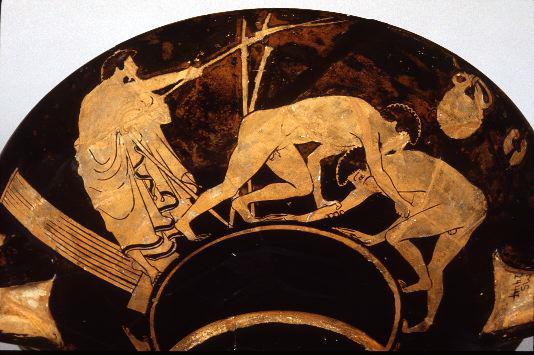

Side A: trainer watching wrestlers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

The ancient Olympics were rather different from the modern Games. There were fewer events, and only free men who spoke Greek could compete, instead of athletes from any country. Also, the games were always held at Olympia instead of moving around to different sites every time.

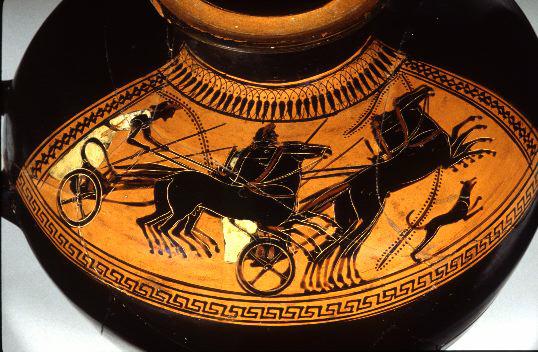

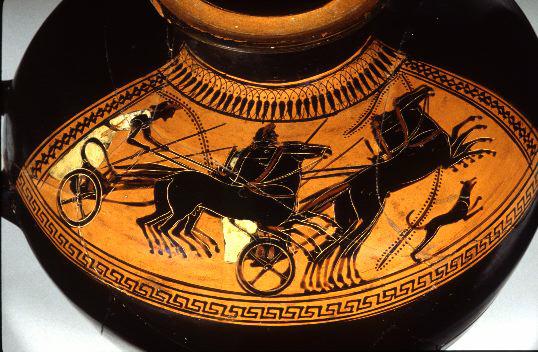

Shoulder: chariot race

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Tampa Museum of Art

Like our Olympics, though, winning athletes were heroes who put their home towns on the map. One young Athenian nobleman defended his political reputation by mentioning how he entered seven chariots in the Olympic chariot-race. This high number of entries made both the aristocrat and Athens look very wealthy and powerful.

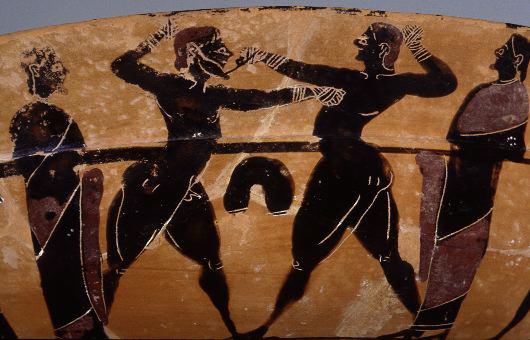

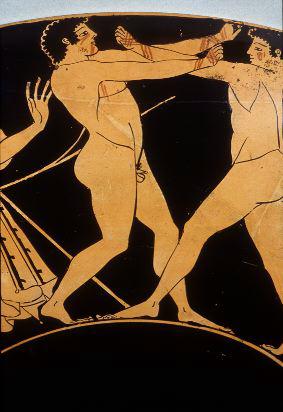

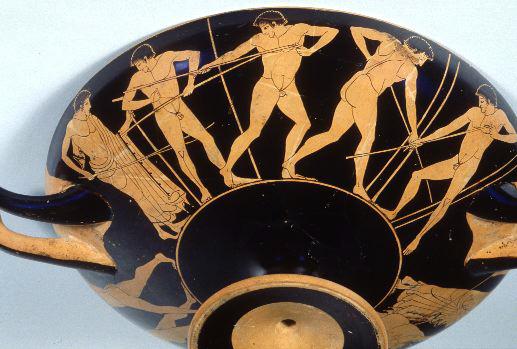

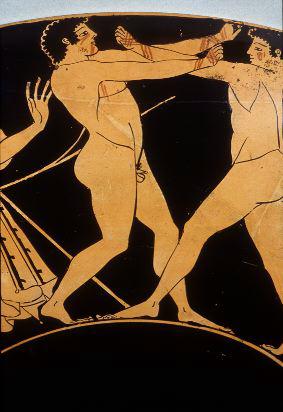

Boxing

Side B: boxers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the University Museums, University of Mississippi

There were no weight classes within the mens' and boys' divisions; opponents for a match were chosen randomly.

Side B: himantes hanging above boxer

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Plato makes fun of boxers' faces, calling them the "folk with the battered ears." Plato, Gorgias 515e.

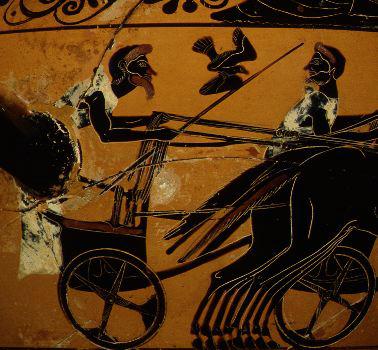

Equestrian events

Side B: scene at center

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

Chariot racing

Side A: charioteer and chariot box at left

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Tampa Museum of Art

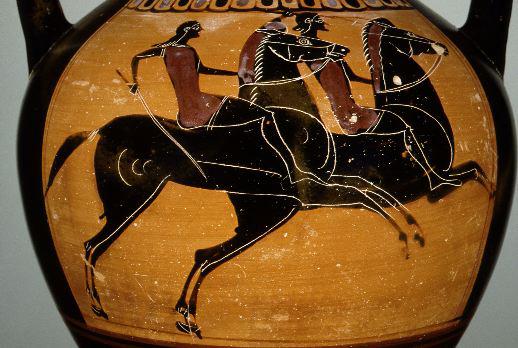

Side B: two riders

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Tampa Museum of Art

Riding

The course was 6 laps around the track (4.5 miles), and there were separate races for full-grown horses and foals. Jockeys rode without stirrups.Only wealthy people could afford to pay for the training, equipment, and feed of both the driver (or jockey) and the horses. As a result, the owner received the olive wreath of victory instead of the driver or jockey.

Shoulder: chariot race

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Tampa Museum of Art

Aristophanes, the comic playwright, describes the troubles of a father whose son has too-expensive tastes in horses: "Creditors are eating me up alive...and all because of this horse-plague!" (Aristophanes, Clouds l.240ff.)

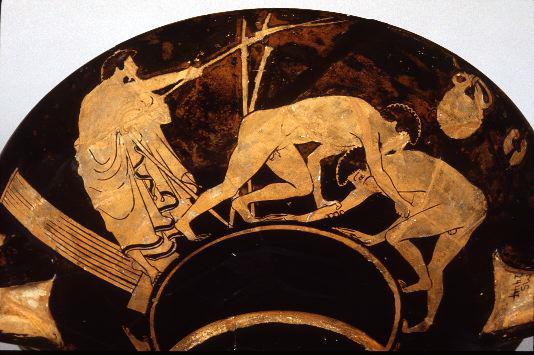

Pankration

Side B: pankration

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Rules outlawed only biting and gouging an opponent's eyes, nose, or mouth with fingernails. Attacks such as kicking an opponent in the belly, which are against the rules in modern sports, were perfectly legal.

Photograph courtesy of Frederick Hemans

The poet Xenophanes describes the pankration as "that new and terrible contest...of all holds" (Xenophanes 2)

Pentathlon

Side A: trainer watching wrestlers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

| Aristotle describes a young man's ultimate physical beauty: "a body capable of enduring all efforts, either of the racecourse or of bodily strength...This is why the athletes in the pentathlon are most beautiful." (Aristotle, Rhetoric 1361b) |

Discus

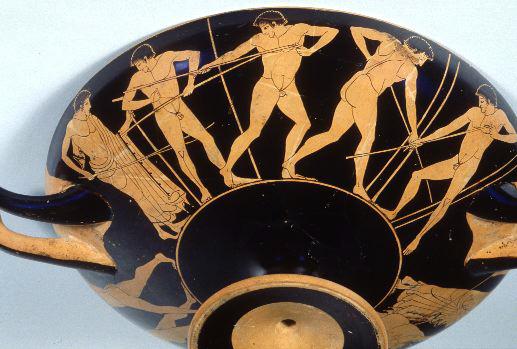

Tondo: discus thrower

Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

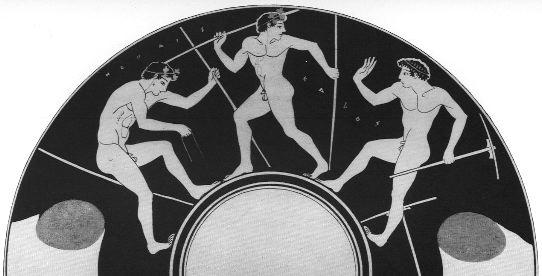

Javelin

Side A: athletes

From Caskey & Beazley, plate XXXVII. With permission of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Side B: youth with javelin, from the waist up

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

Jump

Side A: jumper

Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Side A: diskos bag and halteres above wrestlers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Running

Main panel: runner on right

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

And if these races weren't enough, the Greeks had one particularly grueling event which we lack. There was also a 2 to 4-stade (384 m. to 768 m.) race by athletes in armor. This race was especially useful in building the speed and stamina that Greek men needed during their military service. If we remember that the standard hoplite armor (helmet, shield, and greaves)weighed about 50-60 lbs, it is easy to imagine what such an event must have been like.

Side B: hoplitodromos at left

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

The Phaiacian nobles entertain the hero Odysseus by competing in athletic games: "A course was marked out for them from the turning point, and they all sped swiftly, raising the dust of the plain, but among them noble Clytoneus was far the best at running...he shot to the front and the others were left behind." (Homer, Odyssey 8.121ff.)

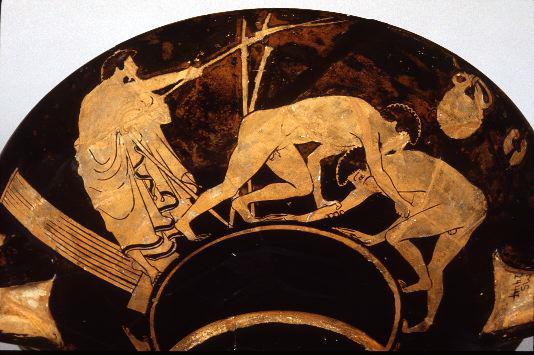

Wrestling

Side A: trainer watching wrestlers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Like the modern sport, an athlete needed to throw his opponent on the ground, landing on a hip, shoulder, or back for a fair fall. 3 throws were necessary to win a match. Biting was not allowed, and genital holds were also illegal. Attacks such as breaking your opponent's fingers were permitted.

Photograph by Michael Bennett

In one of Aristophanes's comedies, one character recommends that another rub his neck with lard in preparation for a heated argument with an adversary. The debater replies, "Spoken like a finished wrestling coach." (Aristophanes, Knights l.490ff.)

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/Olympics/sports.html

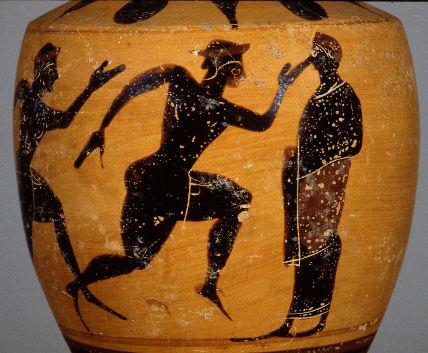

Toledo 1963.26, Attic black figure calyx krater

Side B: Athletes and trainers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

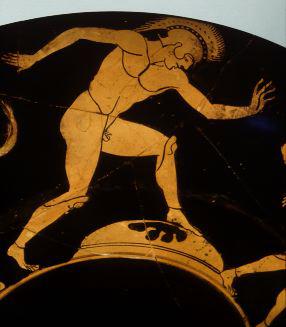

Toledo 1961.26, Attic red figure kylix

Side A: boxer on near right

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

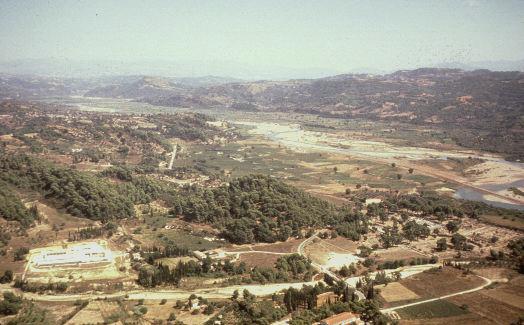

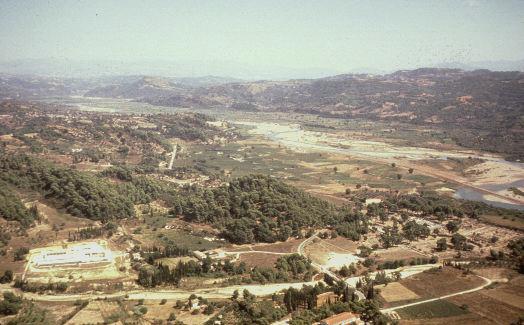

Olympia: Aerial view of site and surroundings, from W

Photograph by Raymond V. Schoder, S.J., courtesy of Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers

Dewing 1125, silver tetradrachm (= 4 drachmas) from Macedonia

Reverse: Zeus seated on throne holding eagle and scepter

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Dewing Numismatic Foundation

In no uncertain terms I must reproach you,

both sides, and rightly. Don't you share a cup

at common altars, for common gods, like brothers,

at the Olympic games, Thermophylai and Delphi?

I needn't list the many, many others.

The world is full of foreigners you could fight,

but it's Greek men and cities you destroy!

AristophanesLysistrata , 1131

Toledo 1963.28, Attic bilingual eye cup

Side A: athletic victor

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Toledo 1961.26, Attic red figure kylix

Side B: javelin throwers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Harvard 1933.54, Attic black figure neck amphora

Side A: scene at center; charioteer crossing finish line

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

Toledo 1980.1022a+b, Attic black figure panel amphora

Side A: four-horse chariot

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Excellence and the competitive spirit

| When the Persian military officer Tigranes "heard that the prize was not money but a crown [of olive], he could not hold his peace, but cried, 'Good heavens, Mardonius, what kind of men are these that you have pitted us against? It is not for money they contend but for glory of achievement!'" Herodotus, Histories , 8.26.3 |

Side B: Athletes and trainers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Ancient athletes competed as individuals, not on national teams, as in the modern Games. The emphasis on individual athletic achievement through public competition was related to the Greek ideal of excellence, called arete. Aristocratic men who attained this ideal, through their outstanding words or deeds, won permanent glory and fame. Those who failed to measure up to this code feared public shame and disgrace.

| Do you think, fellow citizens, that any man would ever have been willing to train for the pancratium or any other of the harder contests in the Olympic games...if the crown were given, not to the best man, but to the man who had successfully intrigued for it? No man would ever have been willing. But as it is, because the reward is rare...and because of the competition and the honor, and the undying fame that victory brings, men are willing to risk their bodies, and at the cost of the most severe discipline to carry the struggle to the end. Aeschines, Against Ctesiphon , 179 |

Not all athletes lived up to this code of excellence. Those who were discovered cheating were fined, and the money was used to make bronze statues of Zeus, which were erected on the road to the stadium. The statues were inscribed with messages describing the offenses, warning others not to cheat, reminding athletes that victory was won by skill and not by money, and emphasizing the Olympic spirit of piety toward the gods and fair competition.

The earliest recorded cheater was Eupolus of Thessaly, who bribed boxers in the 98th Olympiad. Callippus of Athens bought off his competitors in the pentathlon during the 112th festival. Two Egyptian boxers, Didas and Sarapammon, were fined for fixing the outcome of their match at the 226th Olympics. All these men were immortalized as cheaters in the writer Pausanias' 2nd century A.D. guidebook to Greece, in which he describes the statues at Olympia and recounts the men's misdeeds.

Side A: boxer on near right

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

The Olympic truce

A truce (in Greek, ekecheiria, which literally means "holding of hands") was announced before and during each of the Olympic festivals, to allow visitors to travel safely to Olympia. An inscription describing the truce was written on a bronze discus which was displayed at Olympia. During the truce, wars were suspended, armies were prohibited from entering Elis or threatening the Games, and legal disputes and the carrying out of death penalties were forbidden.

Photograph by Raymond V. Schoder, S.J., courtesy of Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers

| Elis is in the northwestern part of the Peloponnese, which is the southern peninsula of mainland Greece. Because it receives more rain, Elis has better forests and pastures than the rest of Greece. The region was respected in ancient times as a holy and neutral place because of the sacred grove to Zeus, called the Altis, at Olympia. |

The Olympic truce was faithfully observed, for the most part, although the historian Thucydides recounts that the Lacedaemonians were banned from participating in the Games, after they attacked a fortress in Lepreum, a town in Elis, during the truce. The Lacedaemonians complained that the truce had not yet been announced at the time of their attack. But the Eleans fined them two thousand minae, two for each soldier, as the law required.

A mina was equivalent to 100 drachmas, and one drachma was an average worker's daily wage, or the price of a sheep. Thus, the fine was a heavy one, equal to 200,000 drachmas.

A mina was equivalent to 100 drachmas, and one drachma was an average worker's daily wage, or the price of a sheep. Thus, the fine was a heavy one, equal to 200,000 drachmas.

Reverse: Zeus seated on throne holding eagle and scepter

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Dewing Numismatic Foundation

Another international truce was enforced during the annual Mysteries, a religious rite held at the major sanctuary site of Eleusis. The truces of Olympia and Eleusis not only allowed worshippers and athletes to travel more safely; they also provided a common basis for peace among the Greeks. Lysistrata, the title character in a comic play by Aristophanes, makes this point when she tries to convince the Athenians and the Spartans to end their war.

In no uncertain terms I must reproach you,

both sides, and rightly. Don't you share a cup

at common altars, for common gods, like brothers,

at the Olympic games, Thermophylai and Delphi?

I needn't list the many, many others.

The world is full of foreigners you could fight,

but it's Greek men and cities you destroy!

AristophanesLysistrata , 1131

The ancient athlete: amateur or professional?

Athletic training was a basic part of every Greek boy's education, and any boy who excelled in sport might set his sights on competing in the Olympics. The Olympic competition included preliminary matches or heats to select the best athletes for the final competition. Ancient writers tell the stories of athletes who worked at other jobs and did not spend all their time in training. For example, one of Alexander the Great's couriers, Philonides, who was from Chersonesus in Crete, once won the pentathlon, which included discus, javelin, long jump, and wrestling competitions as well as running. However, just as in the modern Olympics, an ancient athlete needed mental dedication, top conditioning, and outstanding athletic ability in order to make the cut.

| ...When Hysmon [of Elis] was still a boy he was attacked by a flux in his muscles, and it was in order that by hard exercise he might be a healthy man free from disease that he practised the pentathlon. So his training was also to make him win famous victories in the games. Pausanias, Description of Greece , 6.3.9 |

Side A: athletic victor

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

| Glaucus, the son of Demylus, was a farmer. "The ploughshare one day fell out of the plough, and he fitted it into its place, using his hand as a hammer; Demylus happened to be a spectator of his son's performance, and thereupon brought him to Olympia to box. There Glaucus, inexperienced in boxing, was wounded... and he was thought to be fainting from the number of his wounds. Then they say that his father called out to him, 'Son, the plough touch.' So he dealt his opponent a more violent blow which... brought him the victory. " Pausanias, Description of Greece , 6.10.1 |

Many athletes employed professional trainers to coach them, and they adhered to training and dietary routines much like athletes today. The Greeks debated the proper training methods. Aristotle wrote that overtraining was to be avoided, claiming that when boys trained too young, it actually sapped them of their strength. He believed that three years after puberty should be spent on other studies before a young man turned to athletic exertions, because physical and intellectual development could not occur at the same time.

Side B: javelin throwers

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Victorious athletes were professionals in the sense that they lived off the glory of their achievement ever afterwards. Their hometowns might reward them with free meals for the rest of their lives, cash, tax breaks, honorary appointments, or leadership positions in the community. The victors were memorialized in statues and also in victory odes, commissioned from famous poets.

Did politics ever affect the ancient Games?

Politics were present at the ancient Olympics in many forms. In 365 B.C., the Arcadians and the Pisatans took over the Altis, and they presided over the 104th Olympiad the next year. When the Eleans finally regained control of Olympia, they declared the 104th Games invalid. Some valuable political deeds were recorded at Olympia. An inscription on a victory statue honored Pantarces of Elis not only for winning in the Olympic horse-races, but also for making peace between the Achaeans and the Eleans, and negotiating the release of both sides' prisoners of war.

Side A: scene at center; charioteer crossing finish line

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums

| While the Olympic Games were being celebrated, Alexander had it proclaimed in Olympia that all exiles should return to their cities, except those who had been charged with sacrilege or murder. He selected the oldest of his soldiers who were Macedonians and released them from service; there were ten thousand of these. He learned that many of them were in debt, and in a single day he paid their obligations... Diodorus Siculus, Library , 17.109.1-2 |

Olympia was also a place for announcing political alliances. Thucydides describes a 100-year military treaty the Athenians, Argives, Mantineans, and Eleans entered into, which was recorded in public inscriptions on stone pillars at the first three cities, and on a bronze pillar at Olympia.

| The tyrant of Athens, Pisistratus, exiled Cimon, a wealthy aristocrat, blaming him for a military and political disaster. "While in exile [Cimon] happened to take the Olympic prize in the four-horse chariot...At the next Olympic games he won with the same horses, but permitted Pisistratus to be proclaimed victor, and by resigning the victory to him he came back from exile to his own property under truce." Herodotus, Histories , 6.103.2 |

Side A: four-horse chariot

Photograph by Maria Daniels, courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art